The other day, as I was experimenting with pressure-cooked rice to enjoy with my recent Simple Saag recipe, I thought it was long overdue to discuss the merits of white rice in my diet. I usually mention this every year or two, and I’ve touched on it in each of my books, but it’s always good to open up the discussion from time to time.

The use of rice on a Paleo-friendly website might seem counterintuitive, since most Paleo resources suggest avoiding grains. The reasoning is typically that grains are relative newcomers to humankind’s three-million-year history, since agriculture didn’t spread until the start of the Neolithic era, some 12,000 years ago. But historians estimate that the progenitor of rice existed over 130 million years ago (you know, about 127 million years before humans appeared). It’s so old that similar strains were found in both Africa and Asia, indicating that it was around before the continents first shifted to where they are today.

There is evidence that wild rice was eaten by prehistoric peoples when available, and it was first domesticated around 13,000 years ago, before the end of the Paleolithic era and a couple thousand years before wheat was domesticated. So it’s been around for a long time, much longer that many other foods on our dinner plates – like tomatoes, which were exclusive to South America until about 600 years ago, and cultivated in the Andes only for about 1,000 years prior to that. I’m not picking on tomatoes, because they’re delicious, but you get my point: worldwide, they’ve had 1/12 the culinary lifespan of rice.

Another reason to avoid grains is the fact that many contain low-grade toxins and antinutrients, which can be disruptive to the digestive system. White rice has the lowest toxicity of all the cereal grains, and most of its toxins exist in the bran found in brown rice. A common concern is that grains contain phytic acid, which binds to dietary minerals like zinc and iron, causing them to be less digestible and potentially leading to micronutrient deficiencies. While brown rice carries a significant amount of phytic acid (about the same amount as whole wheat bread), white rice is much lower; in fact, it has less phytic acid than many foods approved by common Paleo diet standards, such as coconut, avocados, walnuts, almonds, and spinach. Finally, the majority of toxins that remain in white rice are destroyed in the cooking process. For this reason, I prefer white rice over brown rice (and it tastes better, too). I like to think of it this way: consider that rice has a reputation among many traditional cultures as being a safe food for digestion, and it is often given to children and the infirm as a way to provide safe, digestible calories. Rice is not nutrient dense, so it’s a good idea to cook it in broth and eat it as part of a nutrient-packed meal; we often top our rice with furikake, a Japanese rice seasoning made from seaweed.

Glycemic load is also a concern when eating rice, and I think my friend Paul Jaminet summed it up perfectly several years ago, here. To paraphrase, the GI of white rice is tempered by a number of factors, including its type (basmati is better than average), cooking method (boiling is best), and the presence of other foods which contain dairy (butter!), fat (meat!), fiber (veggies!), or acids (wine! fermented veggies!). So while the glycemic index on paper looks scary, rice is rarely eaten in a vacuum, but as part of a complete meal.

Last sticking point: it’s true that like other plant-based foods, rice absorbs inorganic arsenic, and there are some pretty frightening reports about the arsenic content found in rice products. First, it’s important to note that the vast majority of rice products with high arsenic content come from brown rice, not white rice. Moreover, the source of your rice is also critical; for example, most rice grown in the US is from Texas, Arkansas, or Louisiana, typically on former cotton fields. Those fields contain high levels of arsenic in their soil, as a result of using pesticides to combat boll weevils, and these rices absorb that arsenic. Alternatively, rice grown in California, East Asia, and South Asia generally contain less arsenic than rice grown in the Southern US. The type of rice also influences its arsenic content, with basmati rice containing the lowest amount of arsenic. While the effects of inorganic arsenic is often disputed, to play it safe, we stick to white rice grown in California or Asia (or Europe, if buying risotto or paella rice).

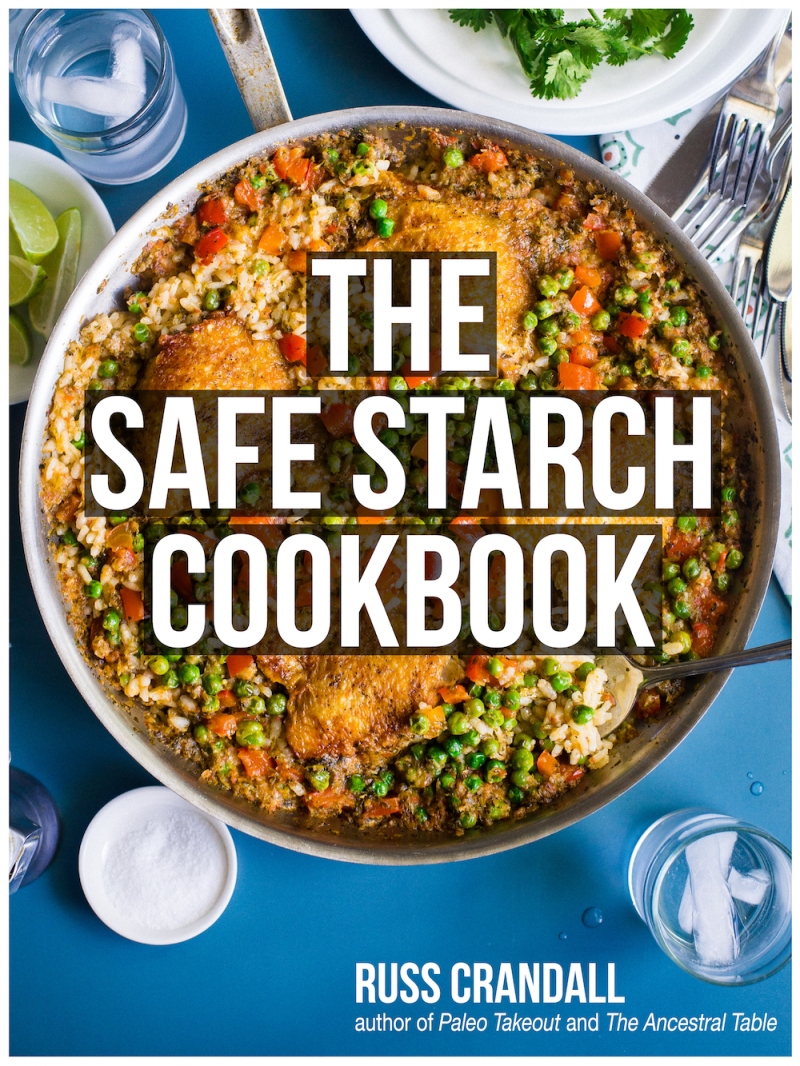

Okay, I hope I’ve made my point, that white rice isn’t some predatory frankenfood that should be avoided at all costs. So let me leave you with one last example: most people would agree that a meal of sautéed chicken, steamed broccoli, and a bit of olive oil is technically “healthy” meal (albeit one that would have me craving pizza afterwards). So how would that meal compare to the flavor, satisfaction, and nutrients found in this Seafood and Sausage Paella, made with broth, seafood, a bunch of veggies, and 1 1/2 cups of white rice spread among six servings? Case closed. Let’s make some rice.

Read Full Article